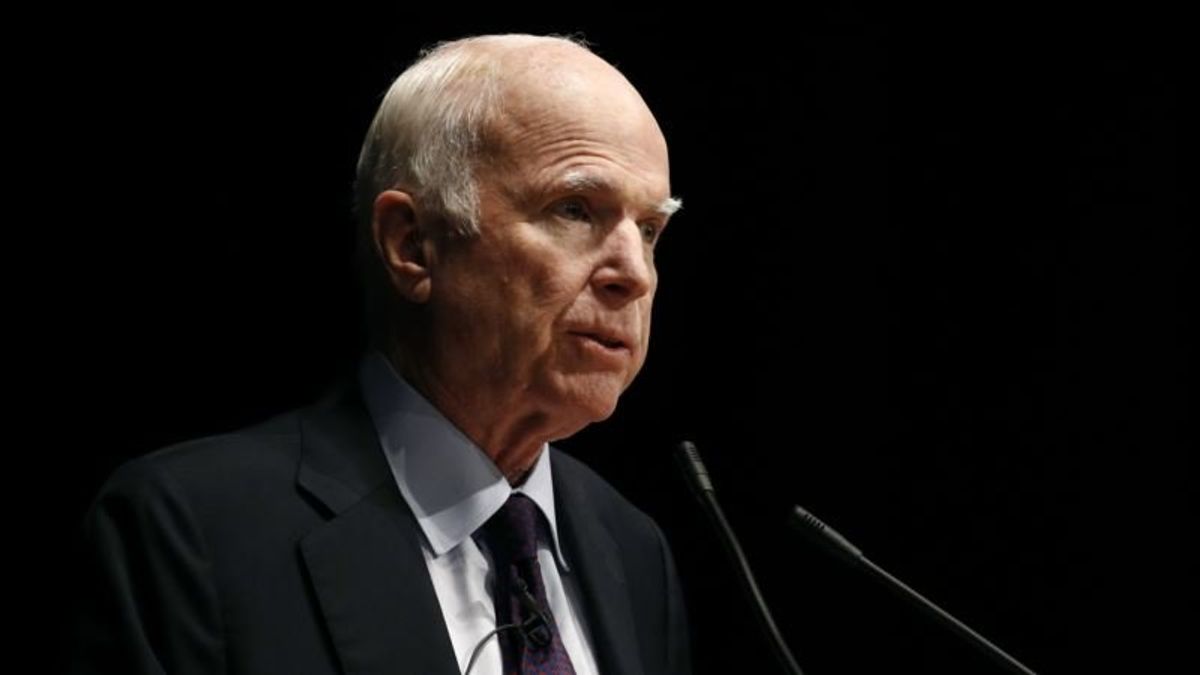

Captivity, Candor and Hard Votes: 9 Moments That Made McCain

Captivity, Candor and Hard Votes: 9 Moments That Made McCain

WASHINGTON —

John McCain lived most of his life in the public eye, surviving war, torture, scandal, political stardom and failure, the enmity of some colleagues and the election of President Donald Trump.

Even brain cancer didn’t seem to scare McCain so much as it sobered and saddened him.

“The world is a fine place and worth fighting for and I hate very much to leave it,” McCain wrote in his memoir, referencing a line from his favorite book, the Ernest Hemingway war novel For Whom the Bell Tolls. ″I hate to leave.”

US Senator, War Hero John McCain Dead at 81

A look at public moments that made McCain:

Prisoner of war, celebrity

McCain, became a public figure at age 31 when his bed-bound image was broadcast from North Vietnam in 1967. The North Vietnamese had figured out that he was the son and grandson of famous American military men — a “crown prince,” they called him. He was offered an early release, but refused. McCain’s captors beat him until he confessed, an episode that first led to shame — and then discovery. McCain has written that that’s when he learned to trust not just his legacy but his own judgment — and his resilience.

Less than a decade after his March 1973 release, McCain was elected to the House as a Republican from Arizona. In 1986, voters there sent him to the Senate.

The Keating Five

He called it “my asterisk” and the worst mistake of his life.

At issue was a pair of 1987 meetings between McCain, four other senators and regulators to get the government to back off a key campaign donor. Charles Keating Jr. wanted McCain and Democratic Sens. Dennis DeConcini of Arizona, Alan Cranston of California, John Glenn of Ohio and Don Riegle of Michigan to get government auditors to stop pressing Keating’s Lincoln Savings and Loan Association. All five denied improper conduct. McCain was cleared of all charges but found to have exercised “poor judgment.”

“His honor was being questioned and that’s nothing that he takes lightly,” said Mark Salter, McCain’s biographer and co-author of his new memoir, The Restless Wave.

The Senate

McCain became his party’s leading voice on matters of war, national security and veterans, and eventually became chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee. He worked with a Democrat to rewrite the nation’s campaign finance laws. He voted for the Iraq War and supported the 2007 surge of forces there even as his own sons served or prepared to serve. But there was one thing that wasn’t as widely known about him: McCain, owner of a ranch in Arizona that is in the flight path of 500 species of migratory birds, became concerned about the environment.

“People associate John with defense and national security, as well they should. But he also had a great concern for and love of the environment,” said Sen. Susan Collins, the Maine Republican who traveled to the ends of the earth with McCain — to the Arctic Circle in 2004 and Antarctica two years later — on fact-finding missions related to climate change. Back on McCain’s Arizona ranch, the senator gave Collins an extensive nature tour of the property. “I particularly remember his love for the birds,” Collins said. “He loved the birds.”

Town halls, Straight Talk

McCain in the 2000 election did something new: He toured New Hampshire on a bus laden with doughnuts and reporters that stopped at “town hall” meetings where voters were invited to exchange views with the candidate. The bus was called the “Straight Talk Express,” and that’s what he promised to deliver at the town halls. The whole thing was messy, unscripted and often hilarious. And ultimately the events re-introduced McCain to voters as a candid and authentic, just a year after President Bill Clinton was acquitted of lying to Congress and obstruction.

In New Hampshire that year, McCain defeated George W. Bush in an 18-point blowout, only to be pushed out of the race in South Carolina. But the town halls remained a fond McCain memory.

“The town halls were festivals of politics,” Salter said. “They were so authentic and open and honest.”

‘No ma’am’

McCain, in 2008 making his second run for president, quickly intervened when a woman in Lakeville, Minnesota, stood at a town hall event and began to make disparaging remarks about Democratic presidential nominee and then-Sen. Barack Obama. “He’s an Arab,” she said, implying he was not an American.

“No ma’am,” McCain said, taking the microphone from her. “He’s a decent, family man, citizen that I just happen to have disagreements with on fundamental issues and that’s what this campaign is all about. He’s not.”

It was a defining moment for McCain as a leader, a reflection of his thinking that partisans should disagree without demonizing each other. But it reflected McCain’s reckoning with the fear pervading his party of Obama, who would go on to become the nation’s first black president.

Cancer

McCain last year was diagnosed with glioblastoma, the same aggressive cancer that had felled his friend, Sen. Edward Kennedy, on Aug. 25, 2009.

Friends and family say he understood the gravity of the diagnosis, but quickly turned to the speech he wanted to give on the Senate floor urging his colleagues to shed the partisanship that had produced gridlock. Face scarred and bruised from surgery, he pounded the lectern. Some of the sternest members of the Senate hugged him, tears in their eyes.

“Of all of the things that have happened in this man’s life, of all of the times that his life could have ended in the ways it could have ended, this (cancer) is by far one of the least threats to him and that’s kind of how he views it,” his son, Jack McCain, told the Arizona Republic in January.

Health care vote

Republicans, driven by Trump, were one vote away from advancing a repeal of Obama’s health care law. Then McCain, scarred from brain surgery, swooped into the Senate chamber and, facing Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, dramatically held up his hand.

The thumb flicked down. Gasps could be heard throughout the staid chamber. McConnell stood motionless, arms crossed.

Trump’s campaign promise — and the premiere item on his agenda — was dead.

Trump

McCain tangled with Trump, who never served in the military, for years.

As a candidate, Trump in 2016 claimed the decorated McCain is only considered a war hero because he had been captured. “He’s not a war hero,” Trump said at an event in Iowa. “I like people who weren’t captured.” Shortly before Election Day in 2016, McCain said he’s rather cast his vote for another Republican, someone who’s “qualified to be president.” Trump fumed, without using McCain’s name, that the senator is the only reason the Affordable Care Act stands.

McCain responded: “I have faced tougher adversaries.”

Senator John McCain Remembered for Courage, Service, PatriotismNext PostCohen Guilty Pleas Encourage Calls for Trump Impeachrment

Senator John McCain Remembered for Courage, Service, PatriotismNext PostCohen Guilty Pleas Encourage Calls for Trump Impeachrment