GOP Unlikely to Reprise Role it Played in Nixon’s 1974 Exit

On Aug. 7, 1974, three top Republican leaders in Congress paid a solemn visit to President Richard Nixon at the White House, bearing the message that he faced near-certain impeachment because of eroding support in his own party on Capitol Hill. Nixon, who’d been entangled in the Watergate scandal for two years, announced his resignation the next day.

Could a similar drama unfold in later stages of the impeachment process that Democrats have now initiated against President Donald Trump? It’s doubtful. In Nixon’s time, there were conservative Democrats and moderate Republicans. Compromise was not treated with scorn.

In today’s highly polarized Washington, bipartisan agreement is a rarity. And Trump has taken over the Republican Party, accruing personal rather than party loyalty and casting the GOP establishment to an ineffectual sideline.

“In the past in the U.S., party members would dissociate themselves from disgraced leaders in order to preserve the party and their own reputations,” said professor Nick Smith, who teaches ethics and political philosophy at the University of New Hampshire. “But now President Trump seems to have such a personal hold on the party — more like a cult leader than a U.S. president — that the exits are closed as the party transforms into his image.”

Congressional leaders

The delegation that visited Nixon was headed by Sen. Barry Goldwater of Arizona, the GOP’s unsuccessful presidential candidate in 1964. Goldwater, who had a long tenure as a party elder, was joined by Sen. Hugh Scott of Pennsylvania, a Republican known for his strong support for civil rights, and Rep. John Rhodes of Arizona — the GOP leaders in their respective chambers.

They told Nixon there were no longer enough Republican votes to spare him from impeachment, given the release two days earlier of a 1972 tape recording contradicting Nixon’s tenacious denial of any role in cover-up of the Watergate break-in.

“He’d been proclaiming his innocence and suddenly they’ve got this evidence showing he’s been lying all this time,” said Thomas Schwartz, a history and political science professor at Vanderbilt University. “We don’t have the equivalent of that now.”

For now, though, Trump has a firewall in the form of Republicans who see more harm in opposing him than supporting him. Cal Jillson, a political science professor at Southern Methodist University, cited the increased political polarization of recent years as a reason most Republican officials will stick with Trump “as long as their own status is not in danger.”

“For the president’s partisans in Congress, it’s ‘our guy on his worst day is better than your guy on his best day,’” Jillson said. “They stick with him to get the judicial appointments, the tax cuts.”

That would change if Trump’s troubles become so serious that congressional leaders think it will affect them and their party, Jillson said.

“Everyone among the Republicans in Congress has a beef with the president but they’re afraid of him,” Jillson said. “If he weakens, that fear will subside.”

A more powerful Congress

The Watergate scandal overlapped with late stages of the Vietnam War, which had bedeviled both Nixon and his Democratic predecessor, Lyndon Johnson. In that era, Congress was more powerful in relation to the executive branch than it is now, with more leaders of national stature, several experts suggested.

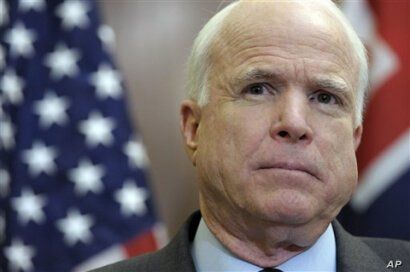

Kathleen Hall Jamieson, director of the University of Pennsylvania’s Annenberg Public Policy Center, suggested that with the death last year of Arizona Sen. John McCain, there’s no Republican currently in Congress who could replicate Goldwater’s 1974 role.

“Who would go and be credible with Donald Trump, so that he would listen?” she asked. “Mitt Romney? Mitch McConnell? Lindsay Graham? Trump will turn on any of them the minute they say something uncongenial.”

A key then-and-now difference, Jamieson said, is that Goldwater represented the same conservative constituency as Nixon and conveyed the message that Nixon was losing its support.

Trump, she said, has a different relationship with his base than Nixon did with his: The base is loyal to Trump personally, rather than to a party establishment.

During Trump’s first two years in office, one of the few Republicans in Congress to tangle regularly with him was Sen. Jeff Flake of Arizona, who decided not to seek reelection in 2018. In a column in The Washington Post on Oct. 1, Flake lambasted his fellow Republicans still in Congress for failure to break with Trump and oppose his reelection.

“At this point, the president’s conduct in office should not surprise us. But truly devastating has been our tolerance of that conduct,” Flake wrote. “From the ordeal of this presidency, perhaps the most horrible — and lasting — effect on our democracy will be that at some point we simply stopped being shocked.”

David Gibbs, a political science professor at the University of Arizona, recalled that Nixon had won reelection by a landslide in 1972, and yet many people who supported him, including Republicans in Congress, were willing to turn against him as evidence of a Watergate conspiracy accumulated.

Loyal no matter what

In contrast, Gibbs now sees the United States as divided 50-50 along the “tribal lines” of Democrats versus Republicans, with Trump’s base remaining loyal no matter what sort of negative picture is painted by his critics.

“The two sides are roughly evenly matched, with neither one able to deliver a knockout blow, and thus there’s political paralysis,” Gibbs said. “The hyper-partisan tribalism makes bipartisan consensus for removing a president virtually impossible.”

Another big change since 1974 is the proliferation of media outlets and the advent of social media, which is used by Trump himself and partisans on all sides to promote their agendas and demonize opponents. Nixon had neither the equivalent of Fox News to support him nor the soapbox of Twitter to accuse his detractors of treason and witch-hunting.

The changing media landscape “has resulted in a political and news environment that moves at light speed compared with the Watergate era,” said David Cohen, a University of Akron political science professor. “The sheer information we are inundated with daily is like drinking out of a fire hose and it is impossible to swallow it all.”

Sen. Bernie Sanders Home in Vermont After Heart AttackNext PostSecond Whistleblower Comes Forward in Trump-Ukraine Scandal

Sen. Bernie Sanders Home in Vermont After Heart AttackNext PostSecond Whistleblower Comes Forward in Trump-Ukraine Scandal