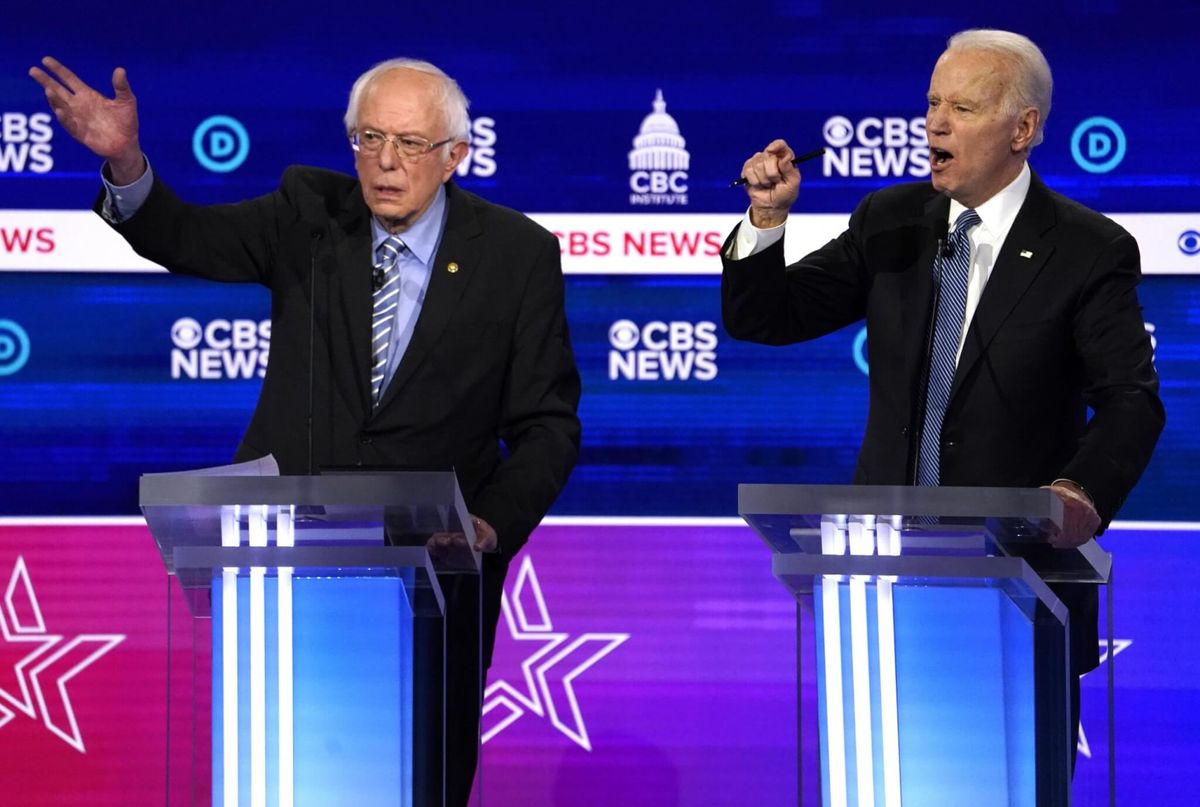

Debate Questions: Biden, Sanders Are Finally to Meet 1-on-1

And then there were two.

Joe Biden and Bernie Sanders are set to meet Sunday night in their first one-to-one presidential primary debate after months of Democratic free-for-alls that presaged a dramatic culling of the field since the opening round of the 2020 race.

Some key questions to look for about the debate, which takes place before the next round of primaries on Tuesday, when 577 delegates are at stake in Arizona, Florida, Illinois and Ohio.

A new opening, but for which candidate?

The coronavirus outbreak has overturned American life, but it is unclear whether the unfolding crisis changes a race that Biden controls with more than half the delegates already awarded.

Both candidates have used the COVID-19 pandemic as a hook to try to justify their main themes, and can be expected to do so again Sunday.

Sanders has been saying that the pandemic demonstrates the need for his "Medicare for All" universal health insurance plan, along with other expansion of a social safety net. He said the shortage of medical goods, from masks and rubber gloves to diagnostic testing kits, is a consequence of decades of establishment trade policy that sent U.S. manufacturing prowess overseas. (Biden, Sanders has noted repeatedly, voted for some of those international trade deals as a Delaware senator.)

To Biden, it's a moment to make the case against President Donald Trump's competence. The former vice president has run against Trump from the beginning, so much so that it cost him embarrassing finishes in early-voting Iowa and New Hampshire. But Biden has rebounded in recent weeks.

On Thursday he outlined his own government-wide coronavirus response during an address in front of American flags, and he introduced a group of blue chip advisers. The unmistakable subtext: a candidate who can already see himself sitting behind the Resolute Desk.

How does a private studio change the dynamics?

Coronavirus forced network host CNN to dispense with a live audience in Phoenix and move the debate to Washington.

Sanders' style is to speak before large audiences, feeding off their energy. Of course, he's also mixed it up with debate audiences, most recently in South Carolina, jeering back when people grumbled at one of his answers.

"Really? Really?" he retorted, gesturing out at the auditorium.

Biden has drawn smaller crowds than Sanders throughout his campaign, but he also has shown more spirit and energy as crowds have gotten larger and friendlier. On Sunday night, the veteran politicians will meet without being able to process how their answers and interactions are playing with any voters listening to them.

So far, the debates have highlighted the overall uneven nature of Biden's campaign. His aides have said for months that he would do better if he got a shot on a smaller stage. Sunday is just that.

How aggressive is Sanders?

Sanders recently shut down a rally crowd that booed Biden. "Nope, nope, nope," Sanders admonished, calling Biden a "friend of mind" who's "wrong on the issues." But will that hold with Sanders now needing 57% of the remaining delegates to win the nomination?

He hasn't been shy about highlighting Biden's record. Sanders has cited Biden's Senate votes for international trade deals, his participation in budget negotiations that would curtail some entitlement spending, his support for the war powers that allowed President George W. Bush to invade Iraq in 2003 and Biden's fundraising from wealthy donors.

But does Sanders only highlight differences and emphasize his own vision? Does he argue simply that Biden's ideas such as tuition-free college for two years instead of four and adding a "public option" to existing health insurance markets rather than replacing private markets with a government system, amount to compromising before the legislative fight even begins?

Or does Sanders risk dividing the party by attacking Biden as another "corporate Democrat" selling out the working class?

Four years ago, when Sanders engaged Hillary Clinton in an extended, bitter battle well after the delegate math favored Clinton, the notion of a Trump presidency was only hypothetical. Now, Sanders and Biden have said repeatedly that neither wants to be viewed as responsible for the president's reelection.

How does Biden reach out?

"Unifying the country" has been a pillar of Biden's campaign. It's mostly a play to independents, centrist Democrats and moderate Republicans worn out by Trump.

But Biden has reached out to the left flank in recent weeks. It's a balancing act given that he has harped on Sanders' identity as a "democratic socialist" and suggested that if Democrats "want a nominee who's a Democrat," they should back Biden.

So what's Biden's approach with Sanders standing nearby? Biden could promote his "progressive" and "bold" agenda to coax voters to his left. He could make the bottom-line appeal about the "common goal" of defeating Trump. Or he could skip the party unity talk altogether.

Down to two older white men

Democrats took the stage last June with a historically diverse field in terms of race, ethnicity, gender, even sexual orientation.

Now the race has come down to two white men each approaching 80. To be fair, Biden and Sanders are the remaining major candidates in no small part because they drew more support from nonwhite voters than any of their rivals.

Yet it's a stark image for a party that prides itself on diversity. Biden, in the South Carolina debate, casually tossed out that he would like to nominate the first black woman to the Supreme Court.

Each candidate talks often about a wide coalition he wants to lead. But how might they acknowledge the juxtaposition of their own identities with the rest of the Democratic Party?

Georgia to Postpone Primaries Over Virus; 2nd State to Do SoNext PostSanders, Biden to Debate Without Studio Audience

Georgia to Postpone Primaries Over Virus; 2nd State to Do SoNext PostSanders, Biden to Debate Without Studio Audience

THE REAL STATE OF THE UNION TONIGHT AT 7PM ET.

Record Stock Market highs. Border secured. Cartels crushed. “America is back.” This is MUST-SEE TV. Wall-to-wall LIVE team coverage starts TUESDAY at 7PM ET on the RAV network!